There’s a belief globally that we have a burgeoning middle class in India – and we’re following in the footsteps of China’s massive change from immense poverty to a stable middle class. But that’s really not the case.

There’s a belief globally that we have a burgeoning middle class in India – and we’re following in the footsteps of China’s massive change from immense poverty to a stable middle class.

But that’s really not the case. There was a very interesting article on Scroll some time back explaining this.

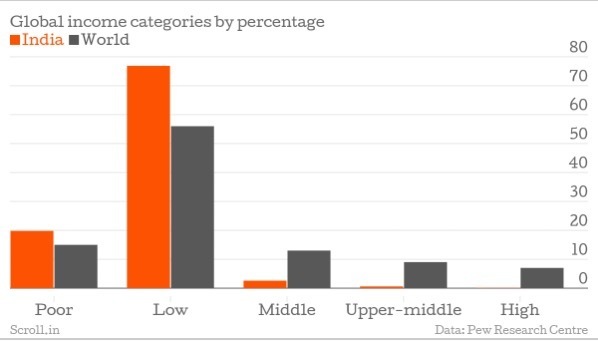

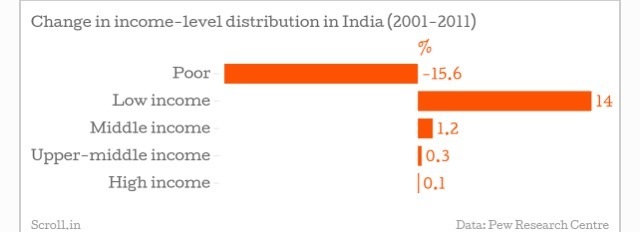

According to the article, “China…saw its middle-income proportion go up from 3% in 2001 to 18% in 2011.” This growth in disposable income, coupled with technology, fueled growth in consumption, most probably with some visibility of profitability for businesses in the country.

In India this hasn’t happened.

“All those stories about India’s burgeoning middle-class have little to do with reality: India is, as it has always been, woefully poor.”

Instead, it seems that the major shift that’s happened is the really really poor are now just poor. And no where close to being determined middle class by any definition. The article does a good job of showing how middle class globally is defined.

Here are a couple of charts showing this move.

We don’t know how fast this low income bracket will start moving into middle income, but my guess is quite slowly. There is a lack of education, lack of opportunities, and lack of incentive for anyone in a position of power to do anything drastic about it. And even if we were motivated, these things take much more time in multi-party democracies like India vs countries like China.

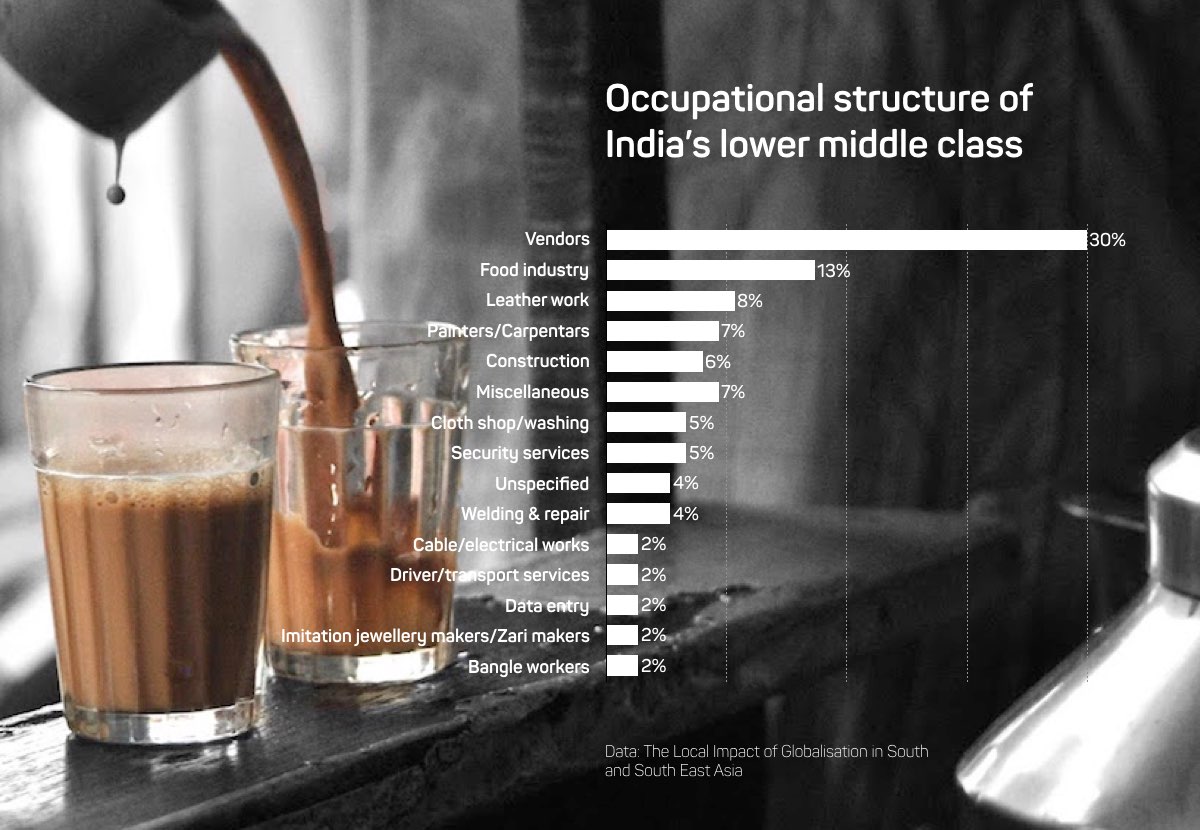

If this is the reality, it’s going to be tougher and tougher for transactional business dealing with consumers (like ecommerce) that make money on delivery/logistics to grow in spite of this long term. Here’s why.

Today, the average take rate (the percentage of each transaction companies make to run their businesses) isn’t sufficient to cover costs related to the transaction. Yet, the take rate as a percentage of the cost of any one item is so high that it’s difficult to imagine most companies being able to increase it. On average companies charge a 10/15% take rate. How realistic is it that any consumer will be willing to pay 25/30/40% extra on top of the cost of an item? Probably not that realistic.

It gets worse. Logistics costs are going up. Believe it or not, ecommerce players have been lucky with overall delivery costs so far. They have spent on everything except their front line. And that’s showing. We’ve seen the repercussions of this at Flipkart already, and things are going to change really fast – starting with delivery staff salaries. So, even increasing take rates (as unrealistic as that sounds) will only help maintain present losses.

Seems like an impossible problem to crack, right? Well, it gets worse because scale doesn’t solve the problem. All these businesses need a substantial offline operational capability. As a result, they get little benefit from growing because they keep needing to add people, delivery centers and other logistics related costs.

And now, to top it off, they’ve been marketing to a middle class that is significantly smaller than was originally imagined. Most people can’t afford as much as online companies need them to – meaning the size of every transaction is only going to get smaller. And since take rates mostly work as a percentage, they’re going to reduce. In fact, it’s very possible that the take rate percentage itself will be under pressure to reduce. And all the while, customer expectations on quality service and delivery will remain the same.

So how do you make up the income? Ad revenue? How realistic is that ad spend in the country will go up any more than marginally anytime soon? How realistic is it that any ancillary revenue streams will make up enough of the short fall? Seems far fetched to me.

It’s actually really unfortunate. There are so many businesses that we truly need in India, but the majority of us can’t afford for them to be as efficient as they are today. How long will this gap in affordability and convenience be funded by private equity? My guess is – not long enough. (But as a consumers, I’m going to enjoy it while it lasts.)

From what I can tell, as bad as the margins are for these businesses, this is the best they will ever be. And that’s scary.